Hindu Marriage Act

Contents of Article

Forms of marriage (8 forms of Hindu marriage before Hindu Marriage act, 1955)

The old textual law provided for 8 forms of marriage, 4 of them were approved and 4 others were unapproved. The legal consequences in both forms of marriage were not similar.

The wife in the approved forms of marriage enjoyed the status of Dharmpatni and all its consequential rights whereas the wife in an unapproved form did not enjoy such status.Moreover the approved forms of marriage were viewed with respect while the unapproved forms were considered to be disgraceful.

The 8 forms of marriage were as under :

- Brahma

- Daiva

- Arsha

- Prajapatya

- Asur

- Gandharva

- Rakshas

- Paishach

The first four of the above (i.e. 1 to 4) were considered to be approved and the latter four (i.e. 5 to 8) were unapproved forms.

Approved forms

Brahma :

In this form of marriage, the father of the girl respectfully invites the bridegroom at his residence, worships him and offers him the girl as his wife along with a pair of fine clothes and ornaments etc. Here the father does not accept any consideration in exchange of bride and does not select the bridegroom with a view to augment his own profession.

A widow could not be remarried under this form of marriage.

Daiva:

In this form of marriage, a well decorated wife is offered to the priest who performs religious acts and rituals for the spiritual benefits of the father of the bride.

Arsha :

In this form of marriage, the bride is offered to a person, from whom the father has accepted a pair of cow or bull for religious rituals only.

Prajapatya :

In this form, the bride’s father, decorating the bride with colourful attires and after worshipping her, offers her to the bridegroom, making a recitation to the effect that they (bride and bridegroom) together may act religiously throughout and prosper and flourish in life.

In this form of marriage, it is not necessary that the bridegroom is a bachelor as against in the Brahma form.

Unapproved forms

Asura :

In this form of marriage, the bridegroom after having given wealth as much as it is within his means to the father and paternal kinsman or to the damsel herself takes her voluntarily as his bride obviously with the consent of her father.

This form of marriage has a striking resemblance with a kind of purchase of bride as the father or the girl herself has already taken money and the father or guardian later giving his consent to marry the girl in lieu of money taken.

Sometimes it is said that in this type of marriage the girl is sold out (Chunnilal v. Suraj, 38 Bom. 433).

The price which the father of the bride gets in consideration of offering bride constitutes his compensation (Govind v. Savitri, 43 Bom. 173).

This type of marriage is practiced widely amongst Sudras of Southern India.

Gandharva :

In this form of marriage, there is a union of the bride and bridegroom by mutual consent motivated by their mutual love and sexual instincts. Infatuated by their bond of love, the bride and the groom establish a bodily union without having performed any religious rites and ceremonies.

One of the leading examples of this type of marriage is found in the famous love story of Dushyant and Shakuntala. Among Kshatriyas, this type of marriage was quite prevalent.

Rakshasa :

In this form of marriage, the girl is forcibly kidnapped and married to a person, who intended to marry her but her father did not agree to it.

There is an attack on the bride’s parents or guardian who is either killed or wounded and thereafter breaking open the door or securing forcible entry into the house, the people at the groom’s side take away the girl, weeping vailing and crying for help.

This type of marriage was prevalent in the Gonda castes of Barrar and Betul (Madhya Pradesh).

Paishach :

According to Dharmashastras, this is the most condemnable form of marriage. In this type of marriage, sexual intercourse is done with a girl, while she is asleep, or brought in a state of drunk or after she is administered some drug and has lost consciousness temporarily or who is of immature understanding.

After the girl is ravished, she is married to one, who has been guilty of such heinous crime.

These eight forms of marriage did not find any place in the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955.

Nature of Marriage under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

Hindu Marriage which was considered to be a religious duty and a sacrament has undergone a change and it has lost its religious sanctity under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, which came into force on 18th May, 1955. The enactment is exhaustive.

The present Hindu Marriage Act has effected certain changes in the law of marriage. It no longer remains a pure sacrament and a binding religious duty. In the sacred texts, marriage created an inseparable tie between the husband and wife, which could not be broken in any circumstances whatsoever, i.e., marriage, was considered to be an eternal union of souls and was indissoluble.

But the HMA, 1955 by providing several matrimonial remedies including mainly divorce and nullity of marriage has seriously eroded its sacramental character.

However, in the case of Pinniti v. State, AIR 1977 AP 48; the Andhra Pradesh High Court maintained that the sacramental character of marriage is still preserved under the Hindu Marriage Act. It was observed by the Court,

“there can be no doubt that a Hindu marriage is a religious ceremony. According to all the texts it is a Sanskaram or sacrament the only one prescribed for purification of soul. It is binding for life because the marriage rites completed by Saptapadi or the walking of seven steps before the consecrated fire creates a religious tie and this religious tie when once created, cannot be broken. The person married may be a minor, or even of unsound mind, and yet, if the marriage rite is duly solemnized, there is a valid marriage.”

In this regard, the Marriage Laws (Amendment) Act, passed in 1976 made another onslaught upon the sacramental character by providing remedies like divorce by mutual consent.

Introduction To Hindu Marriage| Read Here

Nullity of Marriage Under Hindu Marriage Act, 1955| Read Here

Types of Marriages under Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

There are three types of marriages under Hindu Marriage Act, 1955;

- Valid marriage (section 5 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955)

- Void marriage (section 11 of Hindu Marriage Act, 1955)

- Voidable marriage (section 12 of Hindu Marriage Act, 1955)

Capacity to marriage or conditions for a valid Hindu marriage under the Hindu Marriage Act:

Under the HMA, 1955 there are five conditions as pre-requisites for a valid Hindu marriage which are defined under section 5 of the Hindu Marriage Act. These conditions are essential for the validity of marriage. In case of non-fulfillment of these conditions, the marriage would not be deemed to be valid. The conditions given in the section are binding and definite, in absence of which the validity of marriage becomes doubtful (Smt. Rajesh Bhai v. Shanta Bhai, AIR 1982 Bom. 231).

As per section 5 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (Conditions for a Hindu Marriage);

- “A marriage may be solemnized between any two Hindus, if the following conditions are fulfilled, namely:-

- neither party has a spouse living at the time of the marriage;

- at the time of the marriage, neither party-

- is incapable of giving a valid consent to it in consequence of unsoundness of mind; or

- though capable of giving a valid consent, has been suffering from mental disorder of such a kind or to such an extent as to be unfit for marriage and the procreation of children; or

- has been subject to recurrent attacks of insanity or epilepsy;

- the bridegroom has completed the age of twenty-one years and the bride the age of eighteen years at the time of the marriage;

- the parties are not within the degrees of prohibited relationship, unless the custom or usage governing each of them permits of a marriage between the two;

- the parties are not sapindas of each other, unless the custom or usage governing each of them permits of a marriage between the two.

Monogamy (Section 5(i))

Section 5(i) provides the rule of monogamy and prohibits polygamy and polyandry. It now specifies unequivocally that “Hindu can have only one marriage subsisting at a time”. Prior to the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955, a Hindu male could marry more than one wife irrespective of the fact that his previous wife was alive at the time of his subsequent marriage (Veeraswami v. Appaswami, (1863) 1 Mad. HC 231).

Now the section requires that either party to marriage must not have his spouse living at the time of marriage and in the event of breach of this condition, the defaulting party would fall within the ambit of Sections 494 and 495 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 and also would be liable for punishment under Section 17 of the Hindu Marriage Act.

The Supreme Court in the case of Smt. Yamuna Bai Anant Rao Adhav v. Anant Rao Shiva Ram Adhava, AIR 1988 SC 644; had laid down that in the event of breach of first condition specified in Section 5(i) the (second) marriage is rendered null and void under Section 11(1) of the Hindu Marriage Act and since it is void ab initio, the wife cannot claim maintenance under Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

The courts have expressed the view that a party to the bigamous marriage could be punished only upon the proof of the prior marriage having been solemnized according to religious ceremonies and customs (Varadrajan v. State, 1965 SC 50).

The offence of bigamy would be constituted only when at the time of the performance of subsequent marriage, the spouse of such party to marriage was alive and that marriage was not void or invalid. Even where the subsisting marriage was voidable, the offence of bigamy would be made out upon the performance of subsequent marriage. But in every case the offence would be punishable if the essential requirements of law and religion had been duly fulfilled and performed (Priyalata v. Suresh, 1971 SC 1153).

In the case of Shanti Deo Verma v. Kanchan Prasad, AIR 1991 SC 816; the Supreme Court held that by the fact that parties were living like husband and wife and oral evidence to that effect, it cannot be proved that they were validly married and religious ceremonies were duly performed.

In the case of Santosh Kumari v. Surjeet Singh, AIR 1990 HP. 77; the High Court had ruled that even in a case where in her own suit, the wife has obtained a declaration that her husband could remarry during her lifetime, the marriage of her husband with another woman would be illegal despite the consent of his first wife.

The breach of Section 5(i) of the Hindu Marriage Act results in two legal consequences;

- such a marriage would become null and void under Section 11 of the Hindu Marriage Act; and

- the erring party to such a marriage would be liable to be prosecuted under Section 17 of the Hindu Marriage Actand punishment under Sections 494 and 495 of the IPC.

Soundness of mind (Section 5(ii)) :

Section 5(ii) of the Hindu Marriage Act was amended by the Marriage Law Amendment Act, 1976 and the restructured clause lays down as one of the conditions for a Hindu marriage is that neither party must be suffering from unsoundness of mind, mental disorder, insanity or epilepsy at the time of marriage. Section 12(1)(b) renders, at the instance of the aggrieved party, the marriage voidable, if the other party was suffering from any such mental disability at the time of marriage.

The term “at the time of marriage” connotes that if at the time of marriage, the parties to it were of sound mind but later became insane or mentally unsound then this eventuality would not affect the validity of marriage. The Allahabad High Court in the case of Smt. Kiran Bala v. Bhairav Pd., AIR 1982 All; had laid down that a party to marriage must be so much mentally deformed that it becomes impossible for the other party to carry marital life with him or her.

In this respect it would be necessary to establish that such mental disability existed either from before or since the time of marriage. In the event of subsequent mental disabilities in either party to marriage, the aggrieved party can obtain a decree of divorce under the provisions of Section 13 of the Hindu Marriage Act.

If the fact of prior mental disability in either party to marriage had been concealed or had been avoided to be stated by the parents of either party, the marriage could be declared to be void under Section 12(1)(c) of the Act and it would be no defence to plead that it was the duty of the other party to have himself investigated and discovered the truth.

The provisions in Section 5(ii)(a) of the Hindu Marriage Act provides that at the time of marriage neither bride nor the bridegroom be disabled from giving a valid consent to marriage on account of any mental disorder appears to be redundant and suffers from verbosity.

The provisions in Section 5(ii)(b) of the Hindu Marriage Act provides that if the bride or bridegroom is capable of giving a valid consent but suffering from mental disorder of such a kind or to such an extent as to be unfit for marriage and procreation of children, is superfluous and contradictory in terms. A person suffering from any kind of mental disorder of whatever degree becomes unfit for giving a valid consent. Unfitness for marriage and procreation are not at all related to mental disorder.

A mental deformity in any person would not necessarily disable him from producing children. There is no correlation between mental disorder and potency to beget the children.

In Smt. Alka Sharma v. Avinash Chandra, AIR 1991 M.P. 205; the Madhya Pradesh High Court held that the word “and” between expression unfit for marriage and procreation of children in Section 5(ii)(b) should be read as “and”, “or”. The court can nullify the marriage if either condition or both conditions contemplated exist due to mental disorder making living together of parties highly unhappy. In Triveni Singh v. State of UP, AIR 2008 Allahabad High Court; the court held that the annulment of marriage cannot be sought on the ground that either of the parties had HIV infection or any other disease at the time of marriage.

Age of the parties (Section 5(iii)) :

After the Child Marriage Restraint (Amendment) Act, 1978; for a valid marriage the bridegroom must have attained the age of 21 years instead of 18 years as was provided before and the bride must have attained the age of 18 years instead of 15 years as was provided before in the Hindu Marriage Act, at the time of marriage.

A marriage solemnized in violation of Section 5(iii) would not be void although the person the person guilty of the stipulated condition as to the minimum age would be liable to be punished under Section 18(a) of the Hindu Marriage Act(Smt. Naumi v. Narottam, 1963 HP 15 and Mohinder Kaur v. Major Singh, AIR 1972 P & H 184).

In Pinniti Venkatarama v. State, AIR 1977 A.P. 43; the Andhra Pradesh High Court laid down that any marriage solemnized in contravention of Section 5(iii) of the Hindu Marriage Act is neither void nor voidable, the only consequences being that the persons concerned are liable for punishment under Section 18 of the Hindu Marriage Act.

Beyond prohibited degrees (Section 5(iv)) :

Under Section 5(iv), marriages between persons falling within the prohibited degrees of relationship have been prohibited. Section 3(g) defines degrees of prohibited relationship as follows:

Section 3(g) in the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

- Section 3(g) degrees of prohibited relationship

- two persons are said to be within the degrees of prohibited relationship

- if one is a lineal ascendant of the other; or

- if one was the wife or husband of a lineal ascendant or descendant of the other; or

- if one was the wife of the brother or of the father’s or mother’s brother or of the grandfather’s or grandmother’s brother of the other; or

- if the two are brother and sister, uncle and niece, aunt and nephew, or children of brother and sister or of two brothers or of two sisters.

- It is noteworthy that relationship in the above context would also include;

- relationship by half or uterine blood as well as by full blood;

- illegitimate blood relationship as well as legitimate;

- relationship by adoption as well as by blood.

An exception has been made in this clause to the effect that a marriage of persons though related to each other within the prohibited relationship shall be permissible if the custom or usage governing both the parties to the marriage permits a marriage between them. The custom which allows a marriage between persons within prohibited degrees must fulfill the requirements of a valid custom. The custom must not be unreasonable or opposed to public policy (Smt. Sakuntala Devi v. Amar Nath, AIR 1982 P & H 22).

Section 3(g) furnishes details of prohibited relationship according to which a marriage with the following relations cannot result in a lawful wedlock:

A marriage falling within the prohibited degrees of relationship would be void under Section 11 of the Hindu Marriage Act. Moreover Section 18(b) punishes the erring party with the simple imprisonment which may extend upto one month, or with fine which may extend to one thousand rupees, or with both.

Where marriage between persons under prohibited relationship is permitted by custom in a particular community such a marriage would receive the recognition of a valid marriage (Subba v. Seetharaman, (1972) 1 MLJ 497).

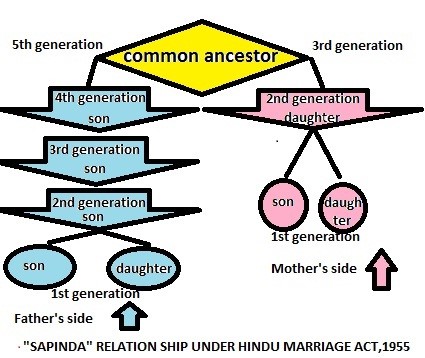

Beyond Sapinda relationship (Section 5(v))

This clause provides that no marriage is valid if it is made between parties who are related to each other as Sapindas unless such marriage is sanctioned by usage or customs governing both the parties. A marriage in violation of this condition will be void and the party violating the provisions of Section 5(v) would be liable to punishment under Section 18(b). The restriction based on Sapinda relationship was applicable ever since before the enforcements of this Hindu Marriage Act (Akshaya Kumar v. Jatindra, AIR 1955 Cal. 612).

If parties to the marriage are governed by such custom which permits marriages between Sapindas, the said prohibition would not apply and the marriage would continue to be valid. The view was expressed by the Punjab High Court recognizing the Sagotra marriage in Vaishya Agrawal community (142 I.C. 211).

The word Sapinda means of the same pinda or having a common “pinda”. A pinda is capable of two meanings, i.e., “particles of body” and “an oblation”.

According to Mitakshara, the word “Sapinda” meant a person connected by the same “panda”, i.e., particles of the same body, i.e., a blood relation. In other words, according to this school, the Sapinda relationship arose from “community of blood” or “community of particles of the same body”.

The Dayabhag, maintained that the relationship arose from a “community in the offering of funeral oblations”, i.e., a person connected by the same pinda, i.e., funeral cake.

In this way, Mitakshara held that the right to inherit arose from propinquity while Dayabhag held that it arose from the capacity to bestow spiritual benefit on the deceased owner.

Section 3(f) in The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

- (i) sapinda relationship with reference to any person extends as far as the third generation (inclusive) in the line of ascent through the mother, and the fifth (inclusive) in the line of ascent through the father, the line being traced upwards in each case from the person concerned, who is to be counted as the first generation;

- (ii) two persons are said to be “sapindas” of each other if one is a lineal ascendant of the other within the limits of sapinda relationship, or if they have a common lineal ascendant who is within the limits of sapinda relationship with reference to each of them;

Marriage ceremonies under the Hindu Marriage Act (Section 7)

Section 7 of the Hindu Marriage Act provides for the essential ceremonies for a Hindu marriage.

Section 7(1) provides that a Hindu marriage must be solemnized in accordance with customary rites and ceremonies of either party thereto and must fulfill the conditions prescribed for the same by Section 5 of the Hindu Marriage Act.

Section 7(2) mentions Saptapadi (i.e., the taking of seven steps by the bridegroom and the bride jointly before the sacred fire) as an essential ceremony for the completion of marriage.

Where observance of Saptapadi is the requirement of neither party to the marriage, the performance of such rituals and ceremonies becomes essential as are accepted by either party. It is only on the performance of such ceremonies and rites that the marriage would become complete and irrevocable (Ravindra Nath v. State, 1969 Cal. 55).

The Supreme Court in Bhaurao Shanker Lokhande v. State of Maharashtra, AIR 1965 SC 1584; held that the word “solemnized” means to celebrate marriage with proper ceremonies and in due form; it, therefore, follows that unless the marriage is celebrated and performed with proper ceremonies and in due form it cannot be said to have been solemnized (Kanwal Ram v. Himachal Pradesh Admn., AIR 1966 SC 614).

The High Courts of Madras and Punjab through the cases of Devani v. Chitambaram, 1954 Mad. 65 and Kanta Devi v. Sri Ram, 1963 P & H 235; have laid down that the performance of two religious ceremonies, i.e.,

Kanyadan, i.e., giving the daughter in marriage

Panigrahan and Saptapadi are essential in every Hindu Community.

Proof of Hindu marriage (Section 8)

In order to facilitate proof of a Hindu marriage the State Government is authorized to make rules providing for registration of marriages as mentioned under Section 8(1) of the Hindu Marriage Act. It further states that such rules must inter alia provide that the parties to any such marriage may have the particulars relating to their marriage entered in the Marriage Register in such manner and subject to such conditions as may be prescribed.

The Section 8(2) states that it is upto the State Government to provide, if it thinks fit, to make the registration of the particulars of all marriages compulsory in the State or in any parts thereof. Where any such direction has been issued by the State Government, any person contravening any rule made in that behalf is punishable with fine which may extend to twenty-five rupees.

Section 8(4) of the Hindu Marriage Act provides that the Marriage Register maintained under the Section and in accordance with the rules made under this Section shall at all reasonable times be open for inspection; moreover it is made admissible as evidence of the statements contained therein.

Section 8(5) provides that notwithstanding anything contained in this Section the validity of any Hindu marriage shall in no way be affected by the omission to make the entry of the marriage. Even if the State Government should make the registration compulsory, the omission to make the entry, whatever other consequences may follow, would not affect the validity of the marriage itself.

Through the case of Seema v. Ashwini Kumar, AIR 2006 SC; the Supreme Court held that the registration of Hindu marriages should be made compulsory.

In the case of Satyam Kumar & Other v. State of UP, AIR 2014 All HC; the Court held that an advocate is never authorized by provision of law to register any marriage or act as marriage officer. The marriage certificate issued by him would be void document.